A spate of recent articles feature opposition to new housing developments in cities ranging from San Rafael, CA to Florence, SC. Opponents cite things like increased traffic and worsening runoff. And yet, the housing crisis deepens.

These stories brought to mind last year’s The New York Times article, “America the Bland,” by Anna Kodé. She critiques multifamily residential projects sprouting up across the country as “anytown architecture,” for lacking regional authenticity and site specificity. It’s easy to lament these ubiquitous, five-over-one buildings; they look cheap and lack character. But, as Kodé points out, we desperately need them—or a better version of them.

Does fear of anytown architecture play into the seemingly rampant opposition to new housing? If so, what’s the antidote to anytown architecture? Four WRNS Studio projects explore some answers.

Brickline: go all in on massing and materiality

Just steps from a regional transit hub and a thriving downtown, Brickline anticipates the continued trend of city dwellers migrating to urban villages just outside of major cities. With easy connections and plenty of choice, walkable suburbs offer the lifestyle that many have come to expect. Through materiality and site specificity, Brickline—which includes a mix of housing, offices, and retail—reads as endemic to the City of San Mateo, with its walkable streets, distinct storefronts, ample open space, and blend of historic and modern architecture. Historic references include Art Deco, Victorian, Spanish Colonial, and Classical Revival.

Paying homage to San Mateo’s distinct sense of place and strong community was important to Prometheus Real Estate Group, a family-owned company dedicated to creating homes and neighborhoods that feel authentic and foster a sense of belonging. Spanning a city block, Brickline is organized in discrete pieces to break down its massing and take cues from the existing streetscape. A combination of brick, wood, and ribbed metal panels differentiate the five-story residences while cream-colored brick and punched windows distinguish the four-story offices, relating in scale and texture to adjacent brick and terracotta clad buildings. Fluted glazed terracotta panels, wood cladding, and a pronounced roof overhang lend additional warmth and variation to the facades. Ground floor retail adds to the city’s offerings while enlivening the street.

The Kelsey Civic Center: embed it in the community

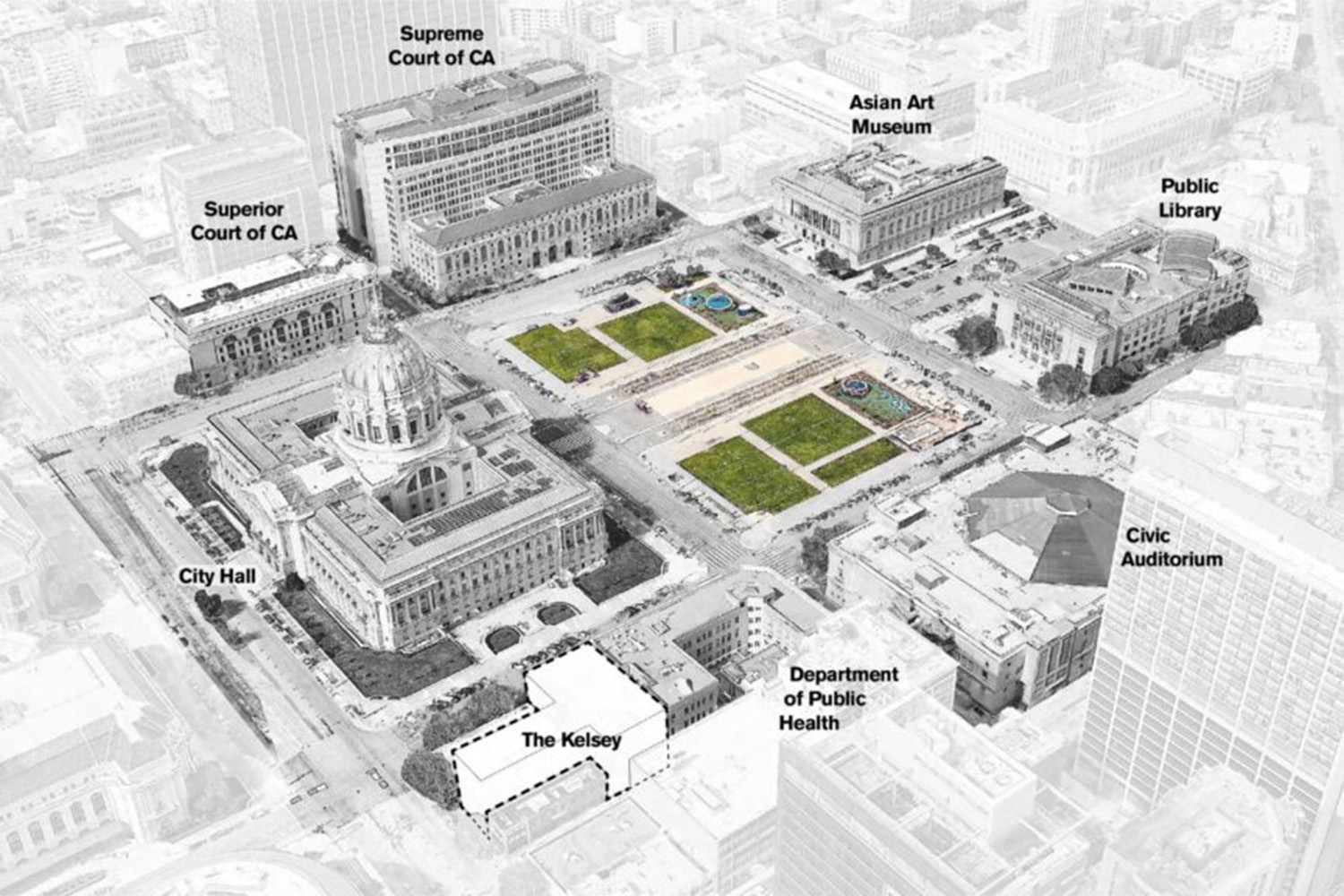

The Kelsey Civic Center is a new urban community that provides 112 homes to people of all abilities, incomes, and backgrounds in one of the nation’s most challenging and inequitable housing markets. Located across from San Francisco’s City Hall, it represents the largest addition to housing for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities in the city to date. The Kelsey Civic Center is part of the C40: Reinventing Cities global initiative, which aims to transform underutilized urban sites into models of social inclusivity, sustainability, and resilience. Universally designed and accessible to all, this carbon-neutral, all-electric building addresses two of the defining issues of our time: the housing and climate crises.

The project sits on an extraordinary site located at the heart of the Civic Center of San Francisco, directly across from City Hall, and close to the Bill Graham Civic Auditorium and the Davies Symphony Hall. Design of The Kelsey Civic Center responds to its existing civic and historical context by reflecting the patterns, materials, and scale of the neighborhood. The building is articulated with a base, middle, and top to complement the massing and organization of the area’s Neoclassical buildings. A three-color fiber cement panel with a stippled texture evokes the neighborhood’s ubiquitous Sierra Granite while anodized copper details echo the area’s accents and secondary features. Double and triple-height fenestration further help the building “hold its own” amidst the weight of its much larger neighboring buildings. With the roof and courtyard visible from many nearby vantage points, including an observation deck at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music, the design team took great care to make the project visually appealing to the broader community.

The ground floor includes a community space that connects to both the public sidewalk on Grove Street and to the central courtyard, allowing views through. The space is entered via a large perforated-metal, hangar-door. This large door ceremoniously folds up and down to showcase a civic-scaled artwork by local artist, Joseph “JD” Green, which was selected by the San Francisco Arts Commission from eleven different submissions that interpreted disability inclusion and racial and social equity. The metal screen’s varying hole sizes recreate Green’s evocative artwork — as well as serve to illuminate and add texture to the interior space, while creating visual interest along the street.

Modera Lake Merritt: activate the street

During the past decade, Oakland’s downtown has emerged as a thriving, mixed-use community that celebrates the area’s rich history. Modera Lake Merritt, a new urban infill residential housing development by Mill Creek Residential, offers much-needed housing near both new and established businesses, while bridging disparate neighborhoods. Nestled between Lake Merritt and the Arts District, Modera Lake Merritt easily connects to transit, retail, and nearby attractions such as the Fox Theater and greenways surrounding a tidal lagoon. The project enlivens the streets day and night, fostering a dynamic, walkable neighborhood.

Situated mid-block, the Modera Lake Merritt gracefully mediates between neighboring structures of varying heights and styles, including a bow-truss warehouse, bulky office buildings, and a high-rise tower. The ground level is transparent and welcoming, seamlessly connecting the building interior with the public realm. A spacious lobby doubles as a resident lounge and co-working space with a fitness center above, all visible to from the sidewalk. Zinc-clad bay windows, balconies, and horizontal bands add depth, character, and variety to the façade, creating interest along the street. The windows and balconies are oriented to connect residents with Oakland’s unique sights and sounds, while providing passersby glimpses of life within. Trees and planters complement the urban greenery around Lake Merritt, further anchoring Modera Lake Merritt in its surroundings and activating the street.

Elco Yards: amplify the public realm

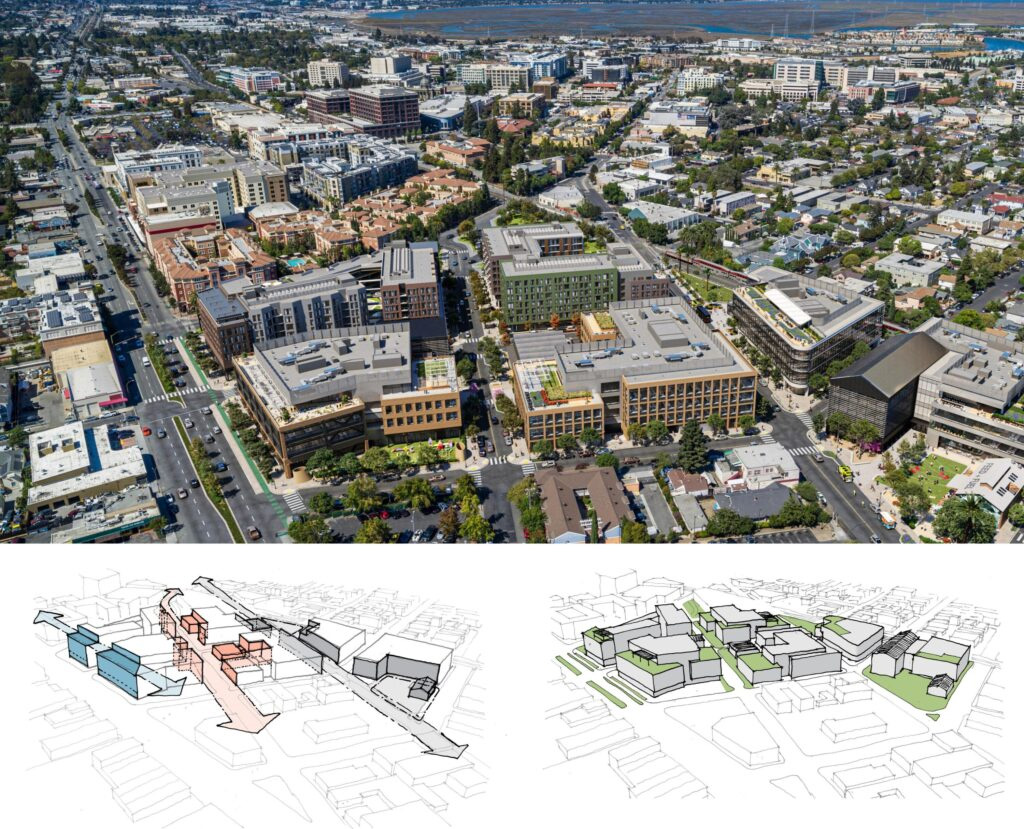

Redwood City is the oldest city on the San Francisco Peninsula and a former Gold Rush port town. One of the region’s centers of commerce, it supported government and manufacturing before declining in the later part of the 20th century. This transit-oriented master plan organizes a variety of flexible live/work environments around open spaces, squares, streets, and pathways that create a vibrant public realm. The renovation of an old feed barn and events lawn creates a gateway to the neighborhood, celebrating the City’s history, ritual, and memory.

A mix of housing, workplace, retail, and public space will attract businesses and benefit the local community. Elco Yards will be walkable, mixed-use, and connected, modeling a more sustainable, urban-minded development pattern for a region growing at a fast and sometimes disconnected clip.

Good urban design

Residential buildings often frame the character and identity of a city while making the streets more walkable and engaging (or not)—and for residents, of course, defining what it means to be at home. These different scales of experience—from the most public to personal—must connect seamlessly for a place to feel authentic. For us, this happens when we investigate the interplay between public and private realms.

How might our projects participate with their cities, making them more connected and memorable? How might we tap into and advance a city’s existing materiality, pathways, and nodes? Can our project help revitalize a nearby park or open space, connecting tenants to nature and recreation as well as their broader community? These questions (and many more) often take us to the right place.

But does good urban design come at a cost premium? We know from experience—as do our peers who specialize in housing—that it doesn’t have to. But it does require a spirit of critical inquiry, technical know-how, and an authentic love of problem-solving. Perhaps most importantly, it takes a genuine curiosity about what makes each place special.

So is anytown architecture better than nothing when it comes to housing? We hope to start re-framing this question.