“FREESPACE encourages reviewing ways of thinking, new ways of seeing the world, of inventing solutions where architecture provides for the well-being and dignity of each citizen of this fragile planet.” – Biennale Architettura 2018

This past July, I spent three days exploring the Venice Biennale, or La Biennale Architettura as it is officially called. For nearly six months, 63 participating countries and over 70 individual architects from around the world come together for perhaps one of the most important platforms for dialog between architects and between architects and the public. With their prompt of “Freespace,” the curators of the 2018 exhibition Yvonne Farrell and Shelly McNamara, founding directors of Grafton Architects based in Dublin Ireland, have chosen design content which “celebrates architecture’s capacity to find unexpected generosity in each project.” They have highlighted projects with an almost primal focus on the quality of space itself. The exhibition emphasizes the “free” gifts of light, air, gravity and materials masterfully put into play in the commercially restrictive environment in which architecture is often created.

Map of La Biennale di Venezia

The exhibition expands beyond the boundaries of any single venue to create the feeling of being coterminous with the city of Venice. Installations are sprinkled across the city; often encountered by surprise as guerilla pop-ups of architectural delight. The individual entries, likewise, broaden the definition of an exhibit to include much more than just content on display. As a point of entry into the comprehensive nature of the Biennale, it is worth pointing out some of the creative and unexpected approaches to each aspect of an exhibit: the venue housing a particular exhibit, the manifesto describing the intent, the techniques used to create the display, and of course the actual content on display. Let me explain with some memorable examples.

“Island” at the British Pavilion

VENUE

It is a special case when a participant can critique or even provide an alternative to the site they are given for their entry into the exhibition. The British Pavilion took this route with one of several early 20th century buildings purpose-built for Biennale events in the Giardini. The entire building interior was left intentionally empty—completely untouched with even some visible residue from previous British exhibitions. Instead, a massive scaffolding wraps around and over the roof, containing a stair and elevator to direct visitors up to the roof. The installation called “Island” is designed by architecture firm Caruso St. John and Marcus Taylor to provide a place of both refuge and exile, inspired in no small way by Brexit and the impending exit from the European Union. The wooden platform viscerally connects with the city of Venice providing nearly 360-degree views. The platform also doubled as an event space, holding various performances, lectures, and events.

The Pavilion of the Holy See

Another radical take on venue was the Vatican, whose inaugural and ambitious entry commissioned 10 world-renowned architects (including two Pritzker Prize winners) each to design a unique chapel in a wooded forest on San Giorgio Maggiore Island, across the lagoon from Piazza San Marco. The number 10 came from the ten commandments, while the architectural brief was to create a new interpretation of Gunnar Asplund’s 1920 Woodland Chapel design. Exploring this single entry became a small journey in itself, first to find the somewhat hidden forest and then to follow the route through the forest to visit each structure.

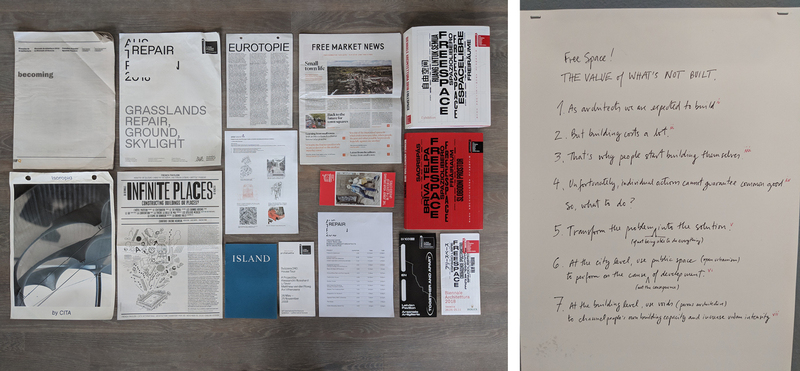

“Free Space: The Value of What’s Not Built” by ELEMENTAL

MANIFESTO

Far from letting an installation speak for itself, many participants provided some sort of written document to explain or propagandize their purpose. These documents varied widely throughout the exhibition from whimsical newspapers and postcards, to posters glued on walls, reminiscent of rock concert or political advertisements. Several followed a more traditional brochure format, but there is nearly as much to read as there was to see. Pritzker Prize winner Alejandro Aravena’s manifesto stood apart as a concise and witty explanation of his approach to engaging communities into the architectural process, and why it benefits our profession overall.

“Unbuilding Walls” at the German Pavillion

DISPLAY

The Biennale’s theme of “Freespace” encouraged each participant to approach their entry as a one-stop exhibition unto itself. For the German Pavilion, human rights activist Marianne Birthler led a curatorial and design team to create “Unbuilding Walls,” a stark, black wall viewed straight-on upon entry into their pavilion. However when stepping to either side, the viewer realizes it isn’t an impenetrable surface but rather an optical illusion of multiple vertical panels offset from each other executed with perspectival accuracy to cleverly conceal individual exhibits on the opposite side.

Display by Paredes Pedrosa Arquitectos

The Spanish firm Paredes Pedrosa Arquitectos crafted layered section models as the pedestals to display a selection of physical models of public buildings. The voids carved out of the solid boards aimed to demonstrate a type of “convex” space, viewed from the outside as defined by light and air.

Weaving Architecture by Benedetta Tagliabue

Benedetta Tagliabue, another Spanish architect, playfully displayed their architectural ideas on fabric pillows casually strewn across the floor. Meanwhile, VTN Architects from Vietnam built a stunning bamboo shade structure midway between exhibits in the Arsenale. Refreshingly placed along a calm lagoon in the center of the former 12th century naval shipyard, the shade provided a pleasant respite to recharge before the next segment of the exhibition.

The Arsenale

CONTENT

As I explored the distinct zones of the Biennale, the brackets of conceptual thought were set wider apart than anything I had experienced. Perhaps this was the intent of “Freespace” as a prompt: to encourage an open and unconfined exploration of architectural thought. Also, the Biennale did not group the exhibits by anything other than the participating country or participating architect’s name. But I did notice some recurring themes and trends that can be drawn out of the massive installation. Some of the most memorable and well-executed entries fell into the categories of transportation, urban futures, sustainability, experiential/immersive displays, explorations of craft, and of course individual building types.

“Station Russia” at the Russian Pavillion

TRANSPORTATION: The Russian Pavilion considered the possibilities of how space might be freed up at the center of cities if railway stations are no longer needed. A series of plaster cast models of Moscow, St. Petersburg, and Kaliningrad show dramatic voids where the main railway station has been removed creating literal “freespace” for new architectural possibilities on the empty lots.

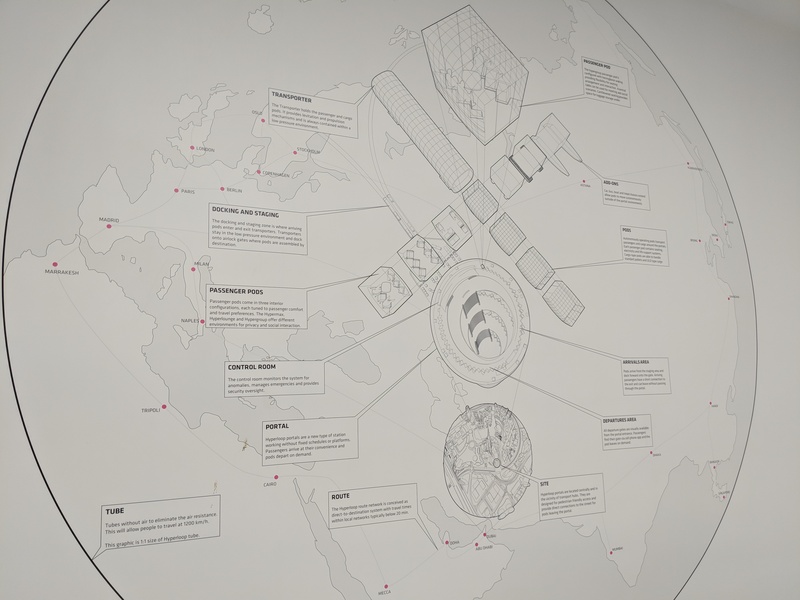

Virgin hyperloop one by BIG, Part of “Possible Spaces – Sustainable Development Through Collaborative Innovations” at the Danish Pavilion

The Danish Pavilion included one exhibit by BIG partnered with Virgin to explain the Hyperloop One concept. Taking Elon Musk’s idea of a passenger pod pushed by pressurized air in a sealed tube, BIG conceptualized a new global transportation network, including ideas for stations, and the transport pods themselves. Virgin began testing the concept in 2016 in the Nevada desert. Virgin and BIG pointed out the serial disruptions of the transportation industry of centuries past, alluding to the hyperloop as the next imminent transportation revolution. Maybe.

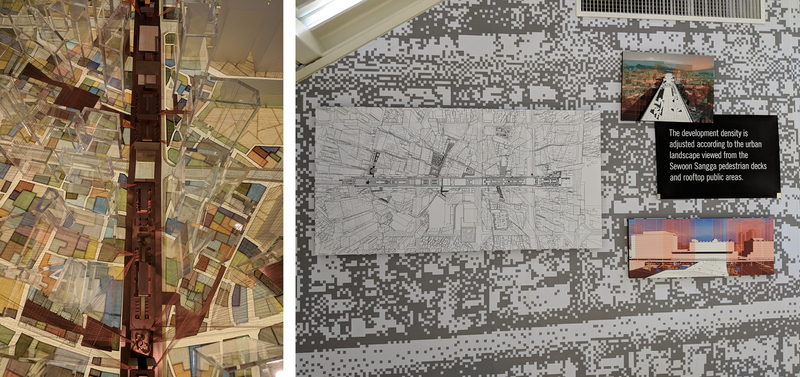

“The City of Radical Shift” at the Korean Pavilion

URBAN FUTURES: Many participating architects and countries took on the question of what becomes of our cities in the near future. The Korean Pavilion held a competition to reconsider the 1960’s Sewoon Sangga complex, a shopping, residential, and industrial mega structure at the heart of Seoul. It has been called the first mixed-use building in Korea. The winning entry by Sungwoo Kim of N.E.E.D Architecture acknowledged the value of the cluster of resources and infrastructure in a city center, while reconceptualizing the complex to add more visual openness, public space, and connections to the landscape. The thesis of the design is to strike a better balance between public and private development interests while maintaining the vitality of downtown areas which have often succumbed to overbuilding by private sector companies. The series of models, drawings, and diagrams made a compelling case.

The entry by Saudi Arabia, designed by local firm Bricklab, offered a simplified, but equally compelling case to think about our urban future through a series of time-lapse-animated line drawings. Each drawing showed an abstracted street map of a different Saudi city, starting from the earliest record of developed roads and extending year-by-year to the present day. The illustration of massive urban growth and the different models of urban organization, even within a single country, was powerfully clear.

“Repair” at the Australian Pavilion

SUSTAINABILITY: The Australian Pavilion, titled “Repair,” focused on the critical role of architecture to utilize and deploy ecological systems. Taking the focus away from architecture as object and replacing it with operational context, Australian artist Linda Tegg partnered with Baracco+Wright Architects to install a living grassland within the pavilion building. While the sensory impact of walking into this room—especially the refreshing smells of nature—are hard to translate into words, the message was clear: architecture has an important role in the environmental, social, and cultural repair of the places it is a part of.

“Archipelago Italia” at the Italian Pavilion

The Italian Pavilion, curated by Mario Cucinella Architects, is titled “Archipelago Italia.” It focused on the spaces in between its urban areas as its most important cultural resource and its differentiating feature as a nation. The comprehensive survey of the Italian landscape encompassed several rooms within the Arsenale. (Apparently the host country gets a little extra space to work with) The idea that landscape becomes its own island in between the cities was illustrated with gradated maps of each territory. While public / private boundaries in cities are often rigid, the exhibition called out the natural features and moments in the countryside when the public and private boundaries are blurred or entirely absent.

“Another Generosity” at the Nordic Pavilion

EXPERIENTIAL/IMMERSIVE: While many pavilions provided evocative content to look at, some went even further to provide an experience that visitors could literally step into and through. The Nordic Pavilion, representing Norway, Sweden, and Finland, also focused on the concept of sustainability but executed their ideas with a group of inflatable structures large enough to walk into. Juulia Kaste, the director of the Finnish Museum of Architecture led a design team including Lunden Architecture Company, Buro Happold Engineering, and Pneumocell Fabrication. They illustrate the connection between air and water, the two elements which mediate between the natural and built environment. As the temperature and humidity change inside and outside of each cellular structure the structure itself expands and relaxes in a constantly changing balance. The effect felt like a living organism “breathing” all around you. The intent was to show how architecture can facilitate a symbiotic relationship between nature and the built environment.

“Cloud Pergola” at the Croatian Pavilion

The Croatian Pavilion combined visual, aural, and experiential elements with their “Cloud Pergola.” The installation had three interwoven parts. Alisa Andrašek, in collaboration with Bruno Juričić, created a “spatial drawing” of thousands of 3D-printed segments forming a cloud-shaped structure resting on three expansive legs. Under the pergola, Vlatka Horvat utilizes bare feet on paper to develop an abstract commentary on the idea of movement and journey. At the same time a sound installation by Maja Kuzmanović creates the ambiance of convivial gatherings under a pergola. In all the installation was an impressive multi-sensory experience.

“House Tour” at the Swiss Pavilion

The Swiss Pavilion was conceived by a design team including Alessandro Bosshard, Li Tavor, Matthew van der Ploeg and Ani Vihervaara. In a playful surprise, they created a house tour where all elements found in the typical swiss home (beautifully minimalist is de rigeur) were dramatically enlarged in scale. Even the door handles.

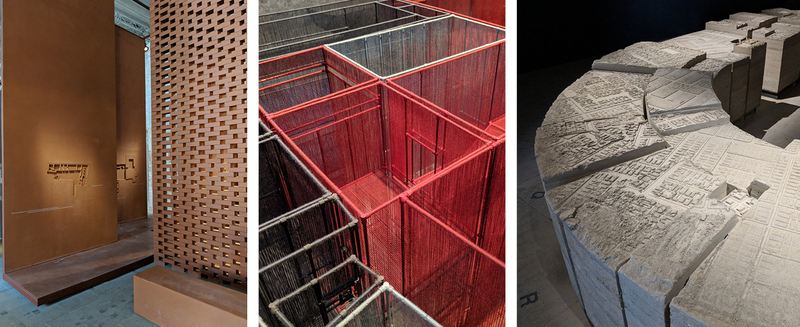

L-R: “Unveil the Hidden” by Maruša Zorec of Arrea Architecture; “Z33 House for Contemporary Art” by Francesca Torzo Architetto; Chile Pavilion curated by Alejandra Celedon

EXPLORATIONS OF CRAFT: Walking through the Arsenale, many of the entries by individual architects and participating nations showcased exquisite craft through different media and techniques used to create the architectural models on display. Maruša Zorec of Arrea Architecture in Slovenia built a brick screen leading into a series of vertical panels where the floor plans of her selected buildings were executed in plaster bas relief. Francesca Torzo Architetto of Italy fused her passion for materiality and model-making with a physical model of a house for contemporary art in Belgium. In the model, the walls are woven from different colored yarn allowing the entire composition to read as a cohesive whole. Her intent was a choreography of spatial sequences moving through the building. The pavilion of Chile included a concrete cast of their national stadium filled with the layouts of shantytowns instead of bleachers. The intent was to tell a double story through a single medium. The stadium was the location of a 1979 operation where ownership was provided to tens of thousands of city dwellers living in fear of constant relocation. The event provided more stability to these city dwellers while acknowledging the close proximity and dissimilar conditions that often coexist in cities. In the medium of architectural model making, the two ideas come together.

“Together and Apart: 100 Years of Living” at the Latvian Pavilion

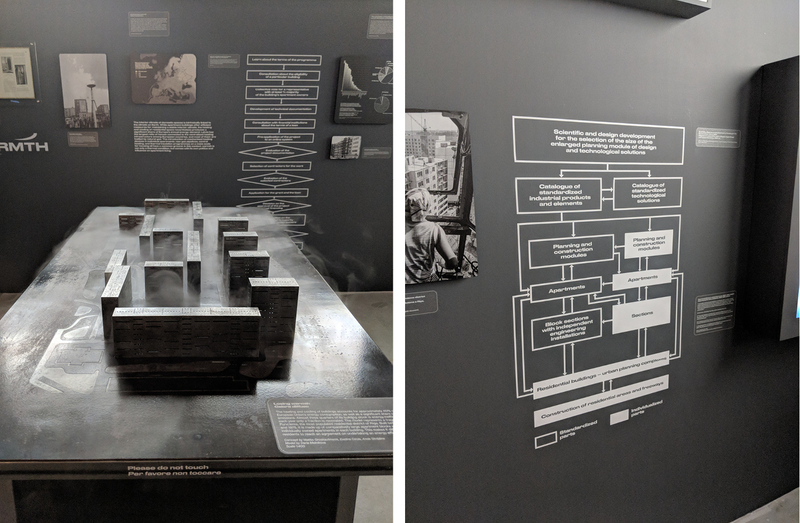

BUILDING TYPOLOGIES: One final theme which appeared in several forms throughout the Biennale was building type studies. Libraries, stadiums, train stations and other building types were explored by different participants throughout the exhibition. The Latvia pavilion, curated by Matiss Groskaufmanis, stood apart with a comprehensive commentary on apartment building design and policy in their country since its independence from the USSR in the 90’s. Two-thirds of the Latvian population resides in apartments, making it the highest ratio in Europe and also a way of life for much of the country. The exhibition examined the political, architectural and technical aspects of different housing solutions that have been tested and deployed over the years. Diagrams illustrated the sometimes convoluted design/construction process and the dire statistics of failed mortgages in recent years while evocative physical models illustrated more technical issues such as maintaining warmth in an often cold country.

In summary, the Biennale was an inspiring roller-coaster ride of architectural possibilities at all scales. The emphasis on holistic thinking is something I connected with personally and have participated in frequently while at WRNS Studio. No matter what the project requirements, schedule, budget, and program demand of us we always take time to investigate deeper and question the spatial problems to reveal the embodied power of architecture and make a visceral connection to a place. The architects’ work on display demonstrate a masterful facility to explain complicated ideas in an original medium. I am proud to be a part of this rich and inventive discipline called architecture.