Shedding Suburban Bias: Anticipating a Vibrant Public Realm

After nearly fifty years of life-changing innovation and creative output, Silicon Valley can still feel vast and desolate. The occasional modern workplace, often insular and opaque, punctuates car-centric roadways, parking lots, and 1980’s office parks. But the past decade has also brought us a big workplace re-think—made all the more salient by post-pandemic trends in hybrid work—as tech companies and private developers compete for employees and tenants with an array of head-turning new campuses. Wood walkways undulate through lush landscapes of native and drought-tolerant plants that summon wildlife. Courtyards, stairways, and occupiable roofs encourage people to socialize and move about. Adaptive reuse, mass timber construction, and innovative stormwater management do good by the environment and its inhabitants. Walkable and connected, many of these new and updated campuses draw inspiration from thriving downtowns.

At the bullseye of this transformation is the City of Mountain View. Home to Google, Microsoft, Intuit, and others, Mountain View foretells a more sustainable development pattern for the Valley. This is not happenstance. In 2012, the City of Mountain View adopted a new General Plan and subsequent Precise Plan, establishing a bold vision for both the City and the tech-heavy North Bayshore Area. The plans set forth a range of improvements, from better mobility to increased housing and habitat preservation. The result is a burgeoning sense of place and community that connects people with one another and with the natural environment.

Change of this nature requires civic leaders who are open and willing to explore new ways of doing things. Two recent WRNS Studio projects show how the City of Mountain View embraces innovation to imagine a better future for the City. As a result, Mountain View is putting the “there” there in Silicon Valley.

A walkable, porous campus

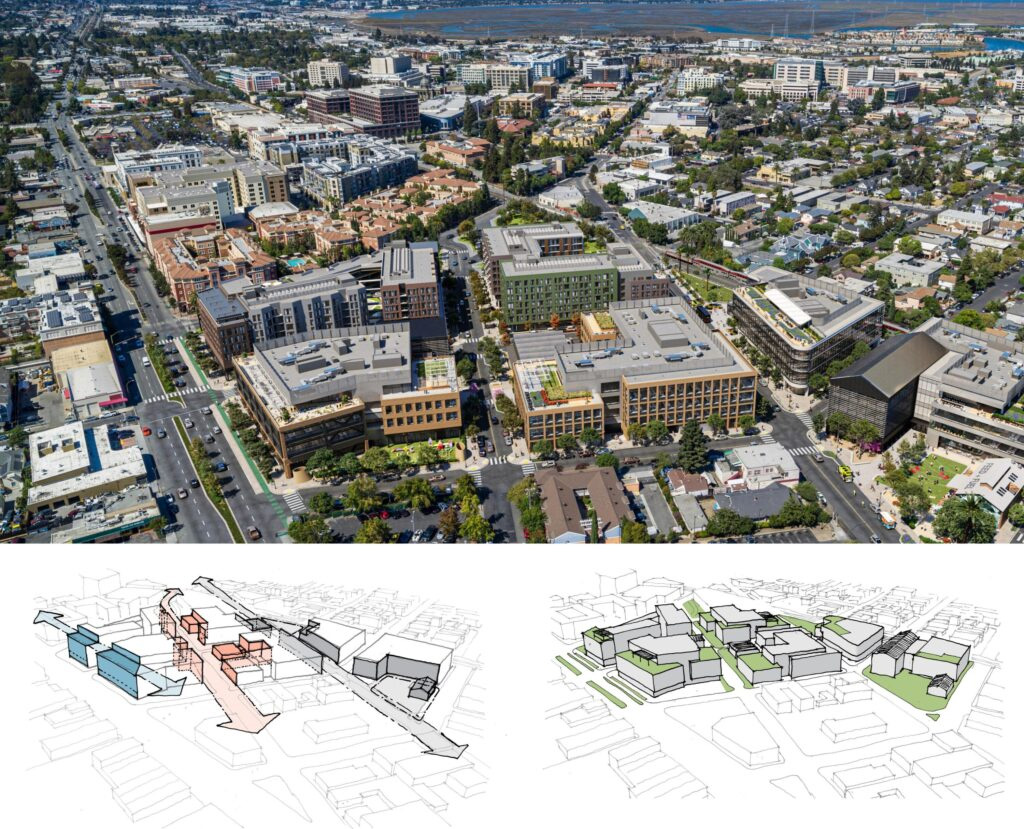

Intuit’s new office buildings help transform this former 1980’s suburban office park into a walkable and porous campus. The planning and geometry of the office buildings can be understood as low, wide, connected, and flexible. With ground floors that emerge from the landscape as solid, textured bases, glassy loft-like upper levels, and extensive terraces, they frame a new campus entry. The buildings create a new center of gravity and strengthen circulation throughout the campus. Design strategies enhance resource efficiency, expand the natural habitat, ensure good indoor environmental quality, reduce water consumption and waste, and enable the expanded use of transit options. How’d we get there? It started with imagining a new kind of place for the City of Mountain View.

Partnering with the City to shape a “middle landscape”

In 2012, when Intuit hired WRNS Studio to update their Mountain View campus with two new office buildings, the City of Mountain View had just begun a new Precise Plan for its North Bayshore Area. Using Intuit as a test case, we worked with Intuit and city planners to redefine how this area will grow by shedding its suburban bias toward cars and insular campuses to incorporate more sustainable, urban design thinking. As both efforts progressed (Intuit campus and Precise Plan) significant interface and consensus building was required to bring definition to each. Our input ranged from metrics to aesthetics, and discussions led to the framework for a new “middle landscape”—not hyper urban, but certainly not suburban either—which took shape on the Intuit campus and was codified in the Precise Plan.

If you build it…

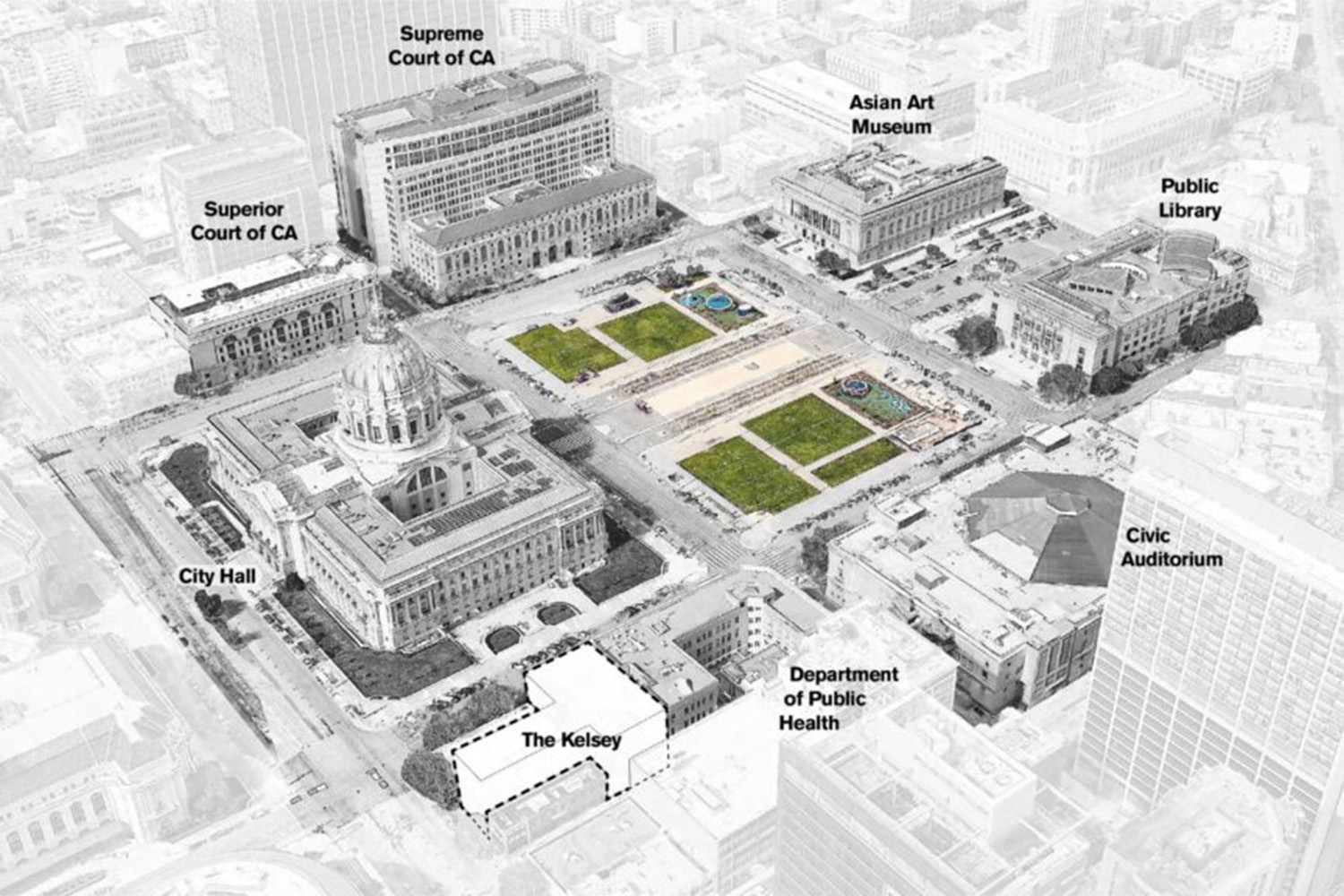

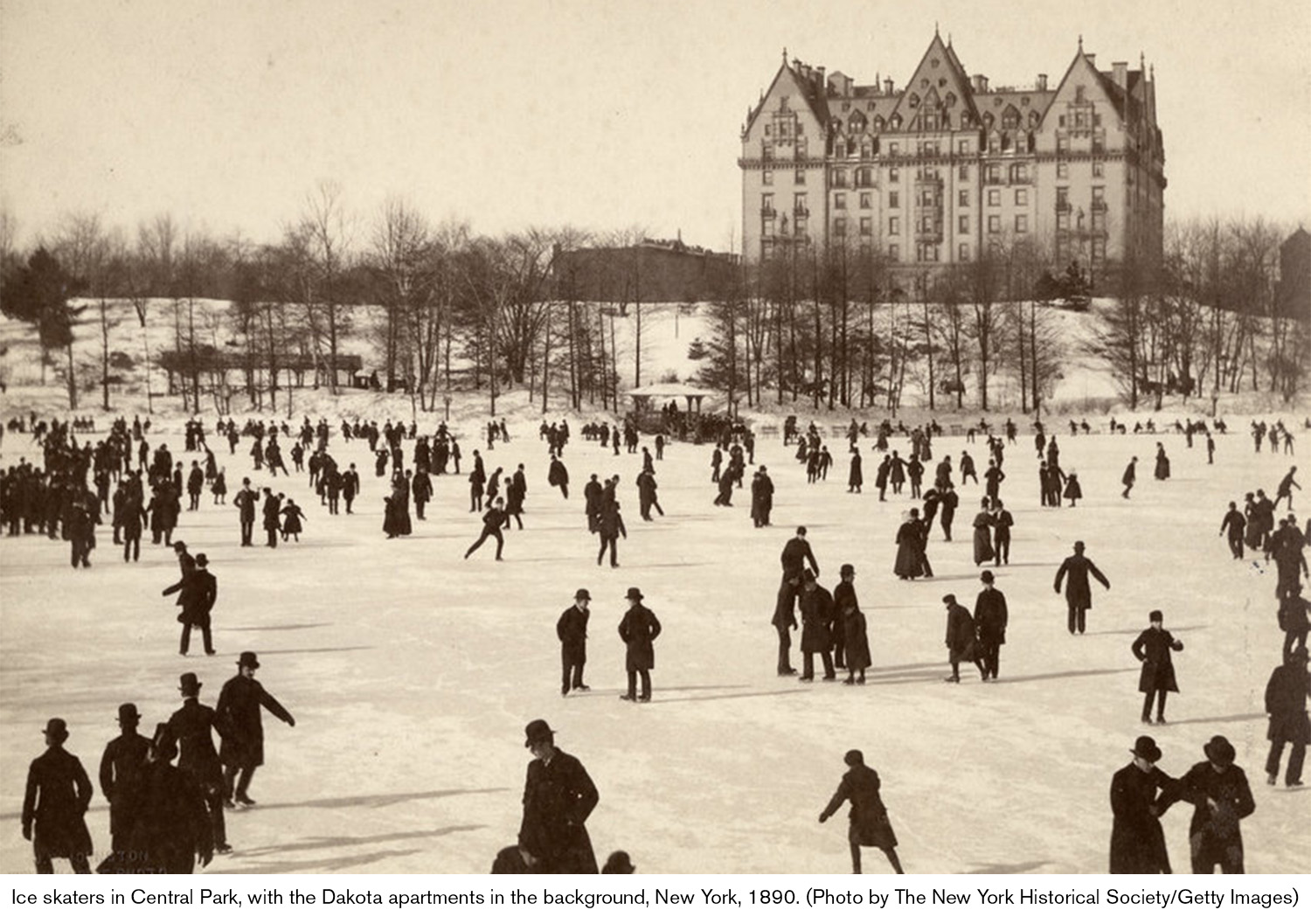

Early in design, the team took inspiration from New York’s iconic Dakota building, overlooking Central Park. Built in 1884, the Dakota marked the Upper West Side’s transition from a rural area dotted with farms and estates to the urban experience many of us know and love today, with its charming brownstones, walkable network of streets, ample connections to nature, and a vibrant public realm.

Activating the public realm

To activate the street, and offer a departure from typical suburban development, we strategically positioned the two office buildings along Garcia Way, fostering a sense of intimacy and guiding pedestrian flows. Anchoring this part of campus is a highly visible atrium that accommodates up to 500 people at a time; it draws activity from the east and west sides of the campus and serves as a hub for the greater Intuit community. Dining and collaborative areas line the building perimeter, further activating the street. Expansive terraces knit the campus together, while helping to sustain local salt marsh and grassland biome species and reducing the burden on the current infrastructure. Signage embedded in the landscape provides educational opportunities about the ecology of nearby tidal estuaries and coastal lowland, further animating the public realm.

Mobility

Regardless of the improvements to the public realm and walkability, no one wants a campus flooded with cars. Anticipating a future in which more people use mass transit, the campus is located within .5 miles of three public bus routes and supported by dedicated shuttle bus drop-offs. To facilitate mobility, the campus features long-term bike storage stalls, short-term racks, floor-mounted EV bike chargers, a bike-sharing program/repair shop, and end-of-ride lockers with showers. A shuttle bus program (MVgo) encourages use of public mass transportation, while providing subsidized pre-tax transit benefits to promote alternative transportation options. Two new parking structures pull concentrate vehicles on the campus periphery.

Rethinking Habitat: Site Ecology and Water

This confidential client’s existing Mountain View campus consisted of five office buildings built in the 1990s. The buildings were arranged in a campus-like setting, with parking lots interspersed between them. Constrained by traffic, environmental degradation, and poor walkability, the project challenges were compounded by California’s ongoing drought. Our client’s imperative to update the campus to support an increase in employees, foster well-being, and model environmental sustainability put a fine point on the need for an integrated approach to planning and design.

Bringing humans and habitat into harmony

Nestled low into the landscape, this updated campus now offers a new kind of workplace—in form, function, aesthetic, and connection—that is first and foremost about the wellbeing and symbiosis of people and place. Designed as a harmonious blend of built and natural environments, the campus features an expansive, accessible living roof and latticework of interconnected courtyards landscaped to help regenerate and support local habitat site ecology. With people moving up staircases, around outdoor decks, and along the roof’s many pathways, the design fosters chance encounters, connectivity, and inclusivity. A national model of environmental sustainability, the project is LEED Platinum, targeting Well Building Standard Gold, and it is Living Building Challenge Net Zero Carbon and Water Petal Certification Ready.

Site ecology

A regenerative approach, informed by the area’s pre-industrialization condition, resulted in the reintroduction of native ecology and restoration of the nearby Stevens Creek. Historically, riparian and oak habitats were prevalent in this area; in addition to planting nearly 600 trees, the habitat enhancement along Stevens Creek benefits over 50 species, including migratory songbirds, terrestrial mammals, and butterflies. The project’s network of water-filtering and conveyance mimics and restores Stevens Creek’s natural watershed process to further support local ecology. Stormwater from the campus’s sidewalks, green roof, and landscape moves into and filters through wet meadow biotreatment/retention basins, and infiltrates the banks of Stevens Creek, healing the soil and restoring the natural habitat zone, before flowing into the San Francisco Bay. Improvements to a beloved public trail invite the broader community to enjoy the restored creek and its surroundings.

Water

Despite a 40% increase in employee capacity and tripling the landscape, design reduced water consumption by 57%. Rainwater is captured in two 60,000-gallon pretreatment tanks, filtered, and then stored in blending tanks. Building wastewater is collected, then treated through a series of packed-bed filters, vertical wetlands, membrane filters, and ozone and UV disinfection before it is stored in the blending tanks.

The campus features an on-site water treatment facility designed to achieve net-positive water usage, with plans in place to meet 100% of potable water needs pending regulatory approval. This pioneering approach required collaboration with city officials, fostering a spirit of innovation and setting a precedent for future water management practices in Mountain View. Visible filter systems, wetlands, and tanks highlight the client’s commitment to ecology and community.

A Thriving Public Realm

As architects and designers who have spent our careers crafting places that impact our communities, we think a lot about the public realm—how it might be enriched through better streets, more open space, improved connections, and restored habitat, to name a few. As shown in the projects above, this commitment can take many built forms. As our towns and cities continue to grow and change, the City of Mountain View offers cues for how to do so intentionally, bringing people and planet into healthier balance, one project at a time.