Addressing a dire need

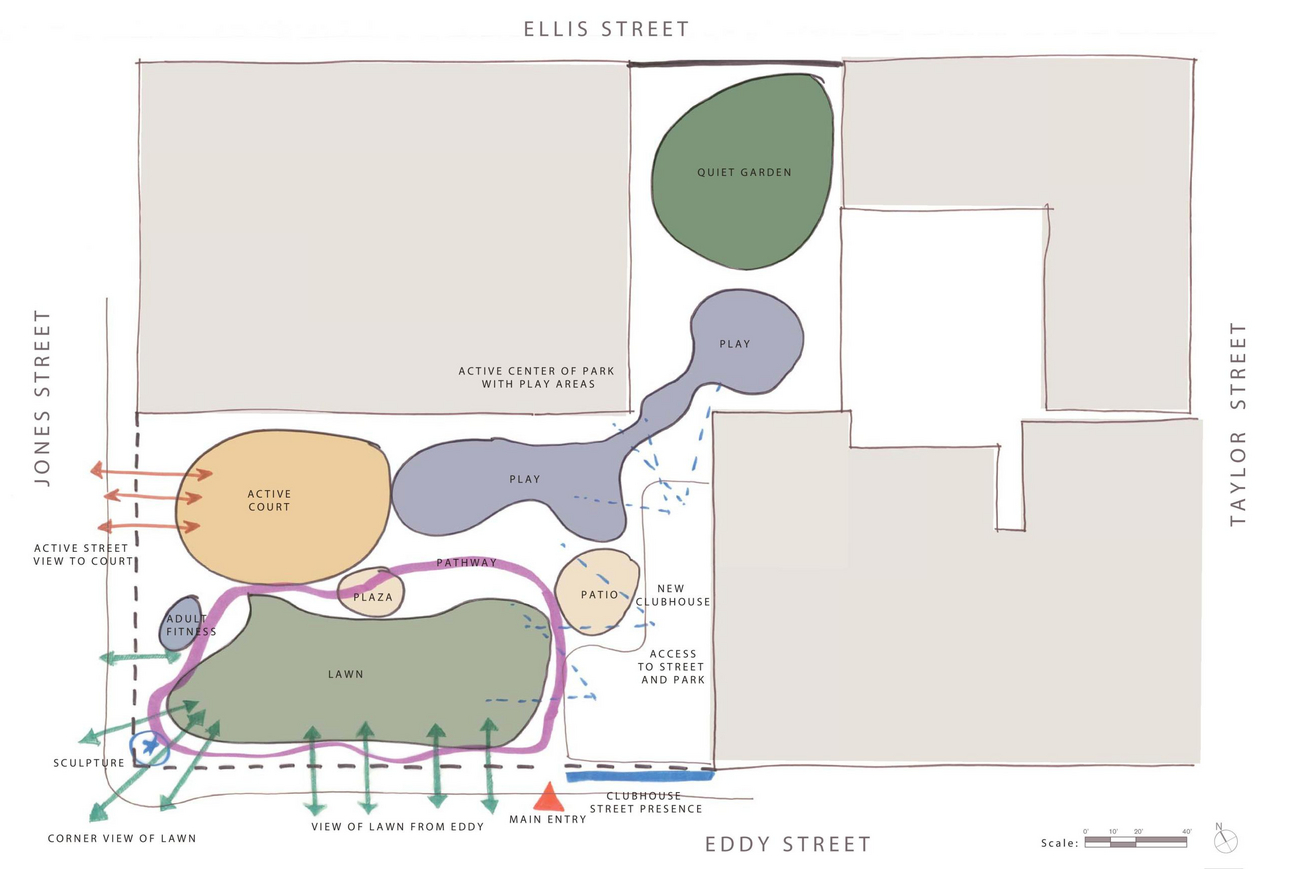

The project advances C40’s Reinventing Cities goals, transforming an underutilized urban site into an inclusive, low-carbon community rooted in health and connection. The courtyard is publicly accessible, creating a shared urban resource in addition to serving residents. The design shows that thoughtful choices, not costly ones, make all the difference in user experience. With an ultra-low EUI and 100% cross-ventilated units, the project demonstrates that performance and design aspiration can align to create housing that fosters belonging and beauty.

Accessibility beyond code

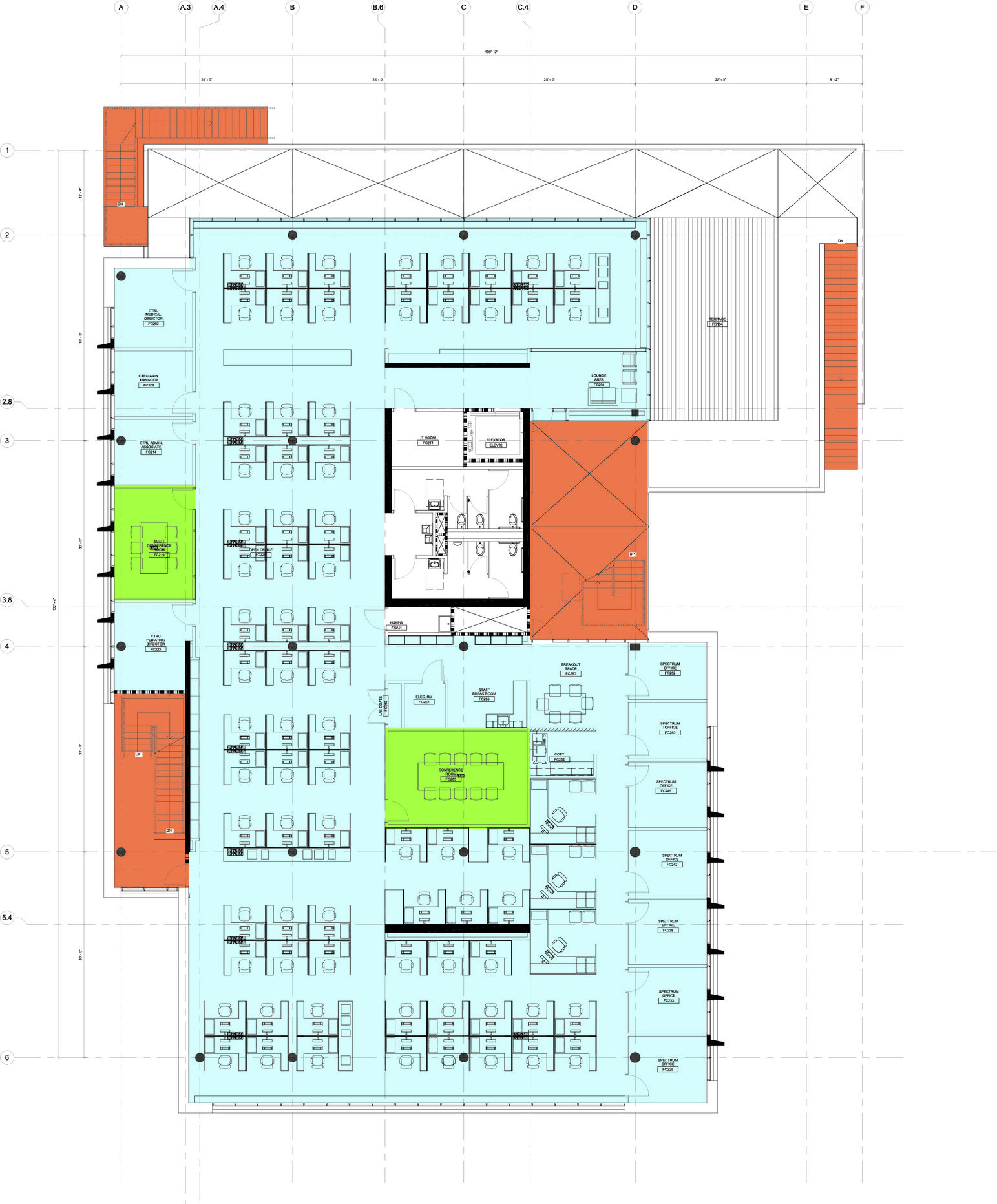

Inclusive design moves beyond code: curved pathways and handrails aid wayfinding, tactile paving and acoustic ceilings create sensory “maps,” and vibrant colors support intuitive orientation. The standards provided interventions relative to mobility and height, hearing and acoustics, vision, health and wellness, cognitive access, and support services. Two onsite ‘Inclusion Concierges’ support residents in building relationships, accessing services, and navigating the neighborhood.

Shaped by the community

Community engagement shaped every aspect of The Kelsey Civic Center—from layout and accessibility to social programming. Focus groups with people with disabilities, their families, and care networks informed design decisions, while a Community Advisory Group, the Golden Gate Regional Center, refined details collaboratively. This process reframed access from code compliance to creativity, elevating disability inclusion as a design driver. It also deepened our practice: inclusive design principles developed here now influence housing, workplace, and beyond. We deepened our understanding of beauty as multisensory—spaces can feel and sound beautiful—and that true inclusion begins with an inclusive process.

Healthy “lungs”

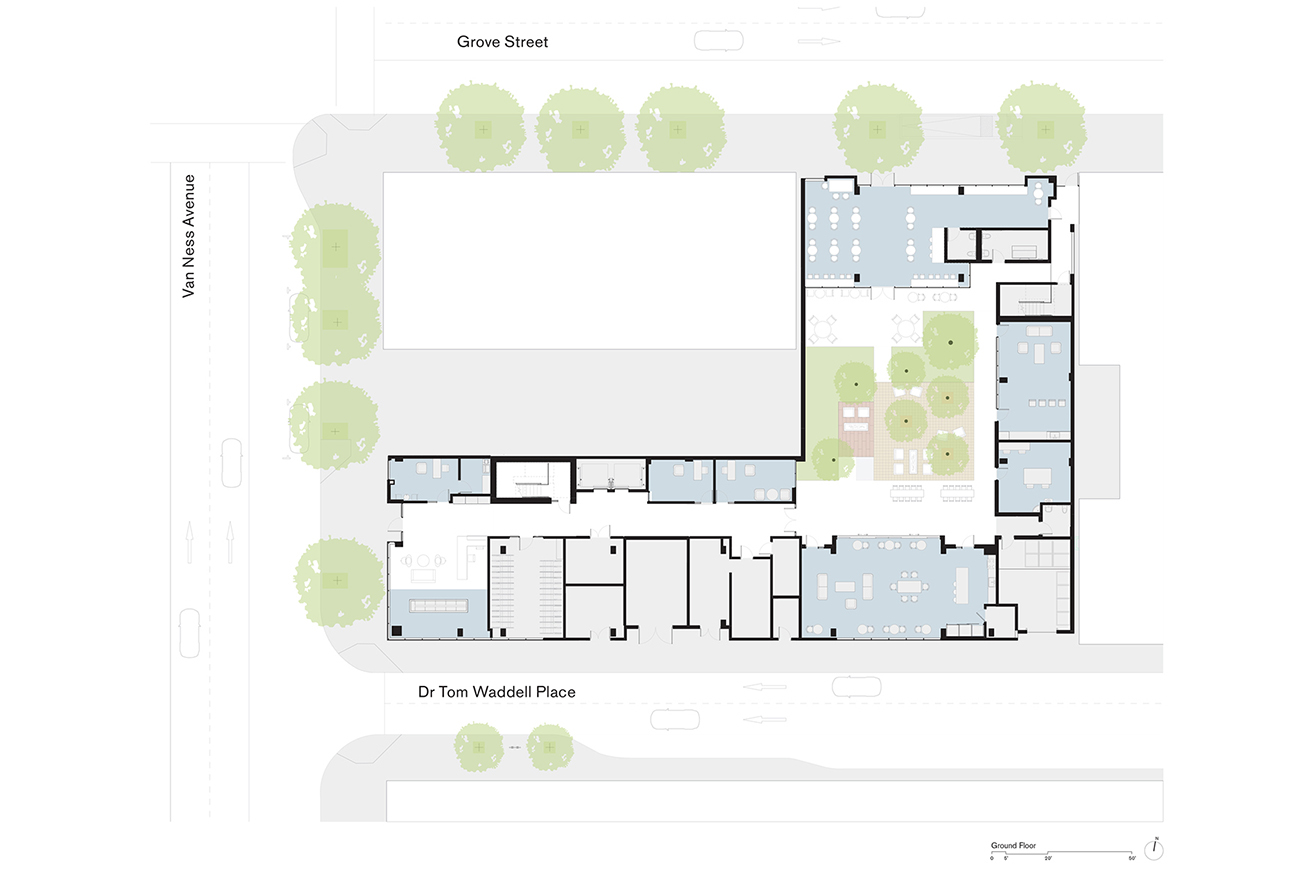

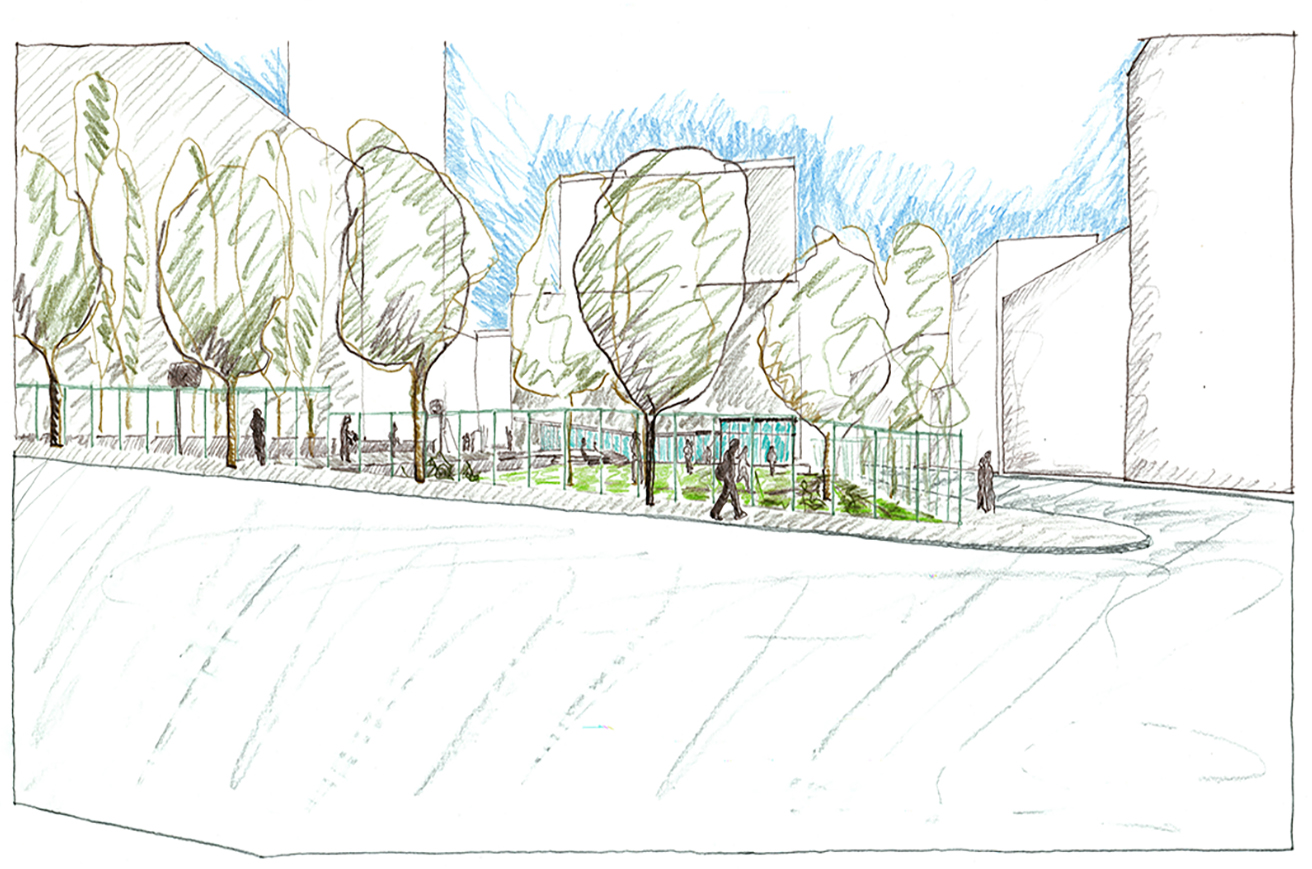

At its heart is the garden courtyard that forms the building’s “lungs,” with seasonal plantings that promote biodiversity, maximizing fresh air, daylight, and nature while creating resilient, low-maintenance, water-conserving, and biodiverse landscapes. Features like exterior walkways, operable windows, and shaded balconies enhance comfort, and energy efficiency through cross ventilation. Spatial daylight analysis optimized the project’s lighting strategies. The rooftop sensory garden supports biophilic principles and fosters a nice break from the urban neighborhood.

All Products were selected through Health Product Declarations (HPDs) and Environmental Product Declarations (EPDs) vetting. Flooring is Red List- and PVC-free, selected to protect residents with chemical sensitivities.

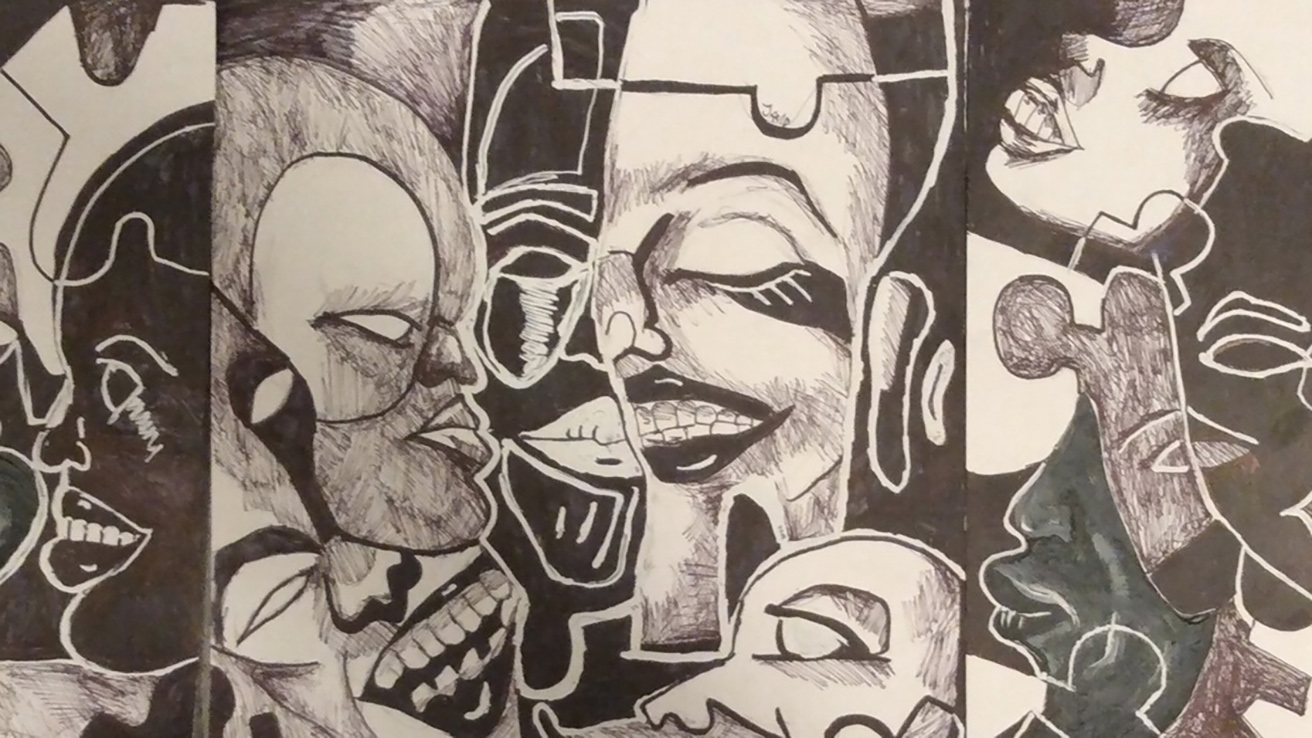

Public art

The ground floor features a community space between Grove Street and the central courtyard. A large perforated-metal hangar door, which ceremoniously folds up to reveal a civic-scale artwork by local artist Joseph “JD” Green, was selected by the San Francisco Arts Commission from eleven different submissions interpreting disability inclusion and racial and social equity. The door’s metal screen, with varying hole sizes, recreates Green’s artwork, adding visual interest along the street while illuminating and texturing the interior.

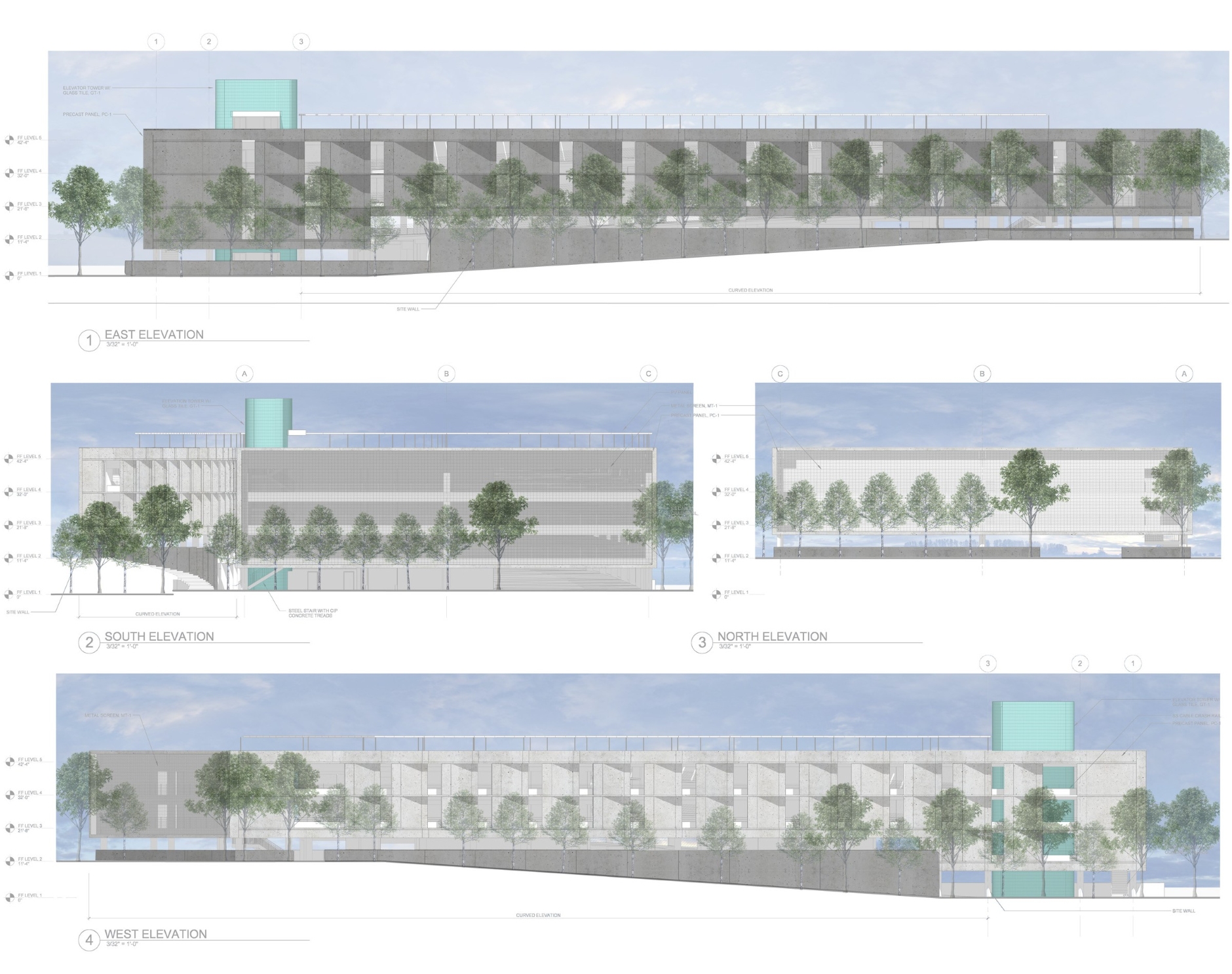

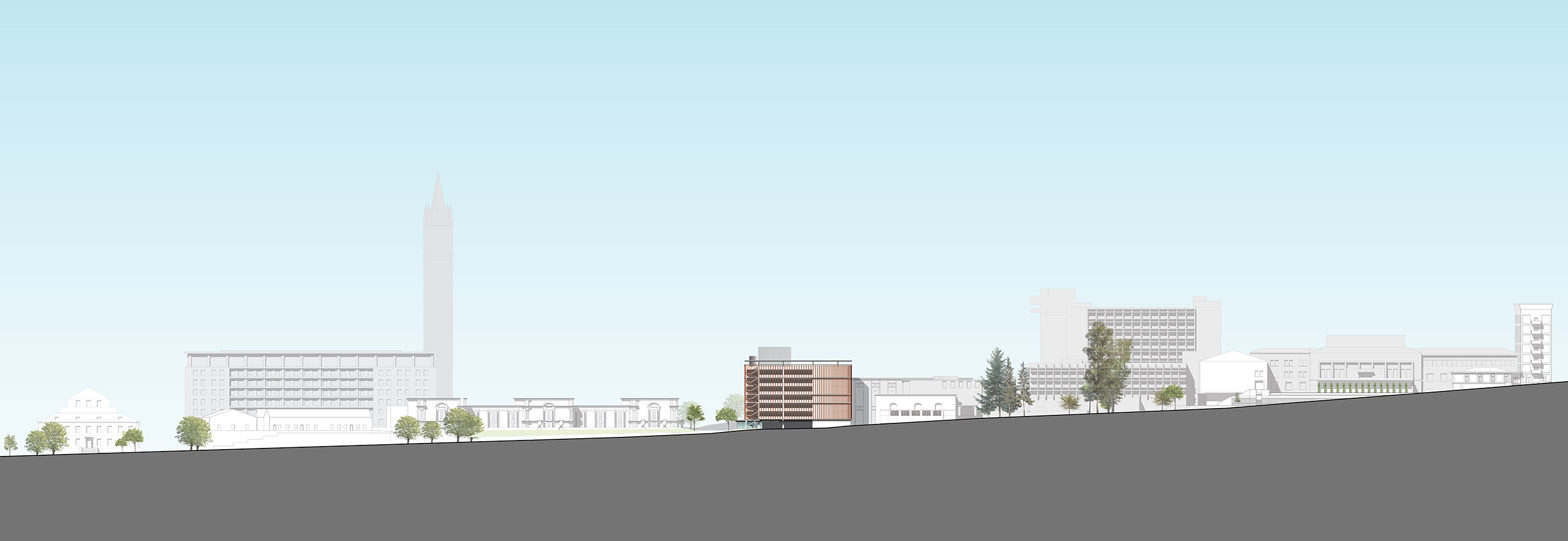

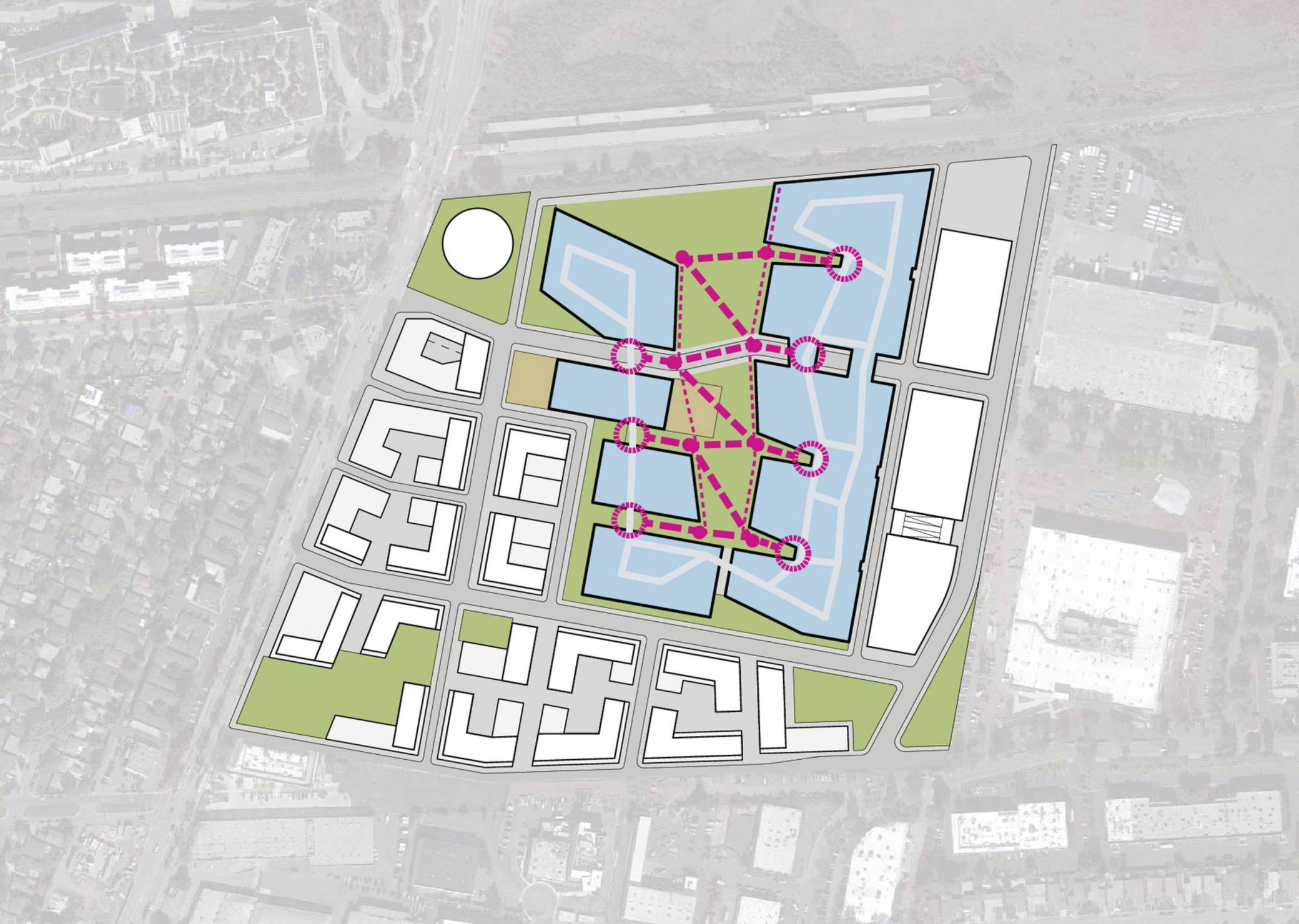

Site-specific design in San Francisco’s civic heart

The project sits at the heart of San Francisco’s Civic Center, directly across from City Hall. Design reflects the civic and historical context through patterns, materials, and scale. The building’s base, middle, and top complement the massing and organization of the neighborhood’s Neoclassical buildings, with a three-color cement board panel evoking Sierra Granite and anodized copper details echoing local accents. Double and triple-height windows ensure the building “holds its own” among larger neighbors. With the roof and courtyard visible from various vantage points, including the San Francisco Conservatory of Music, the design team ensured the project is visually appealing to the broader community.