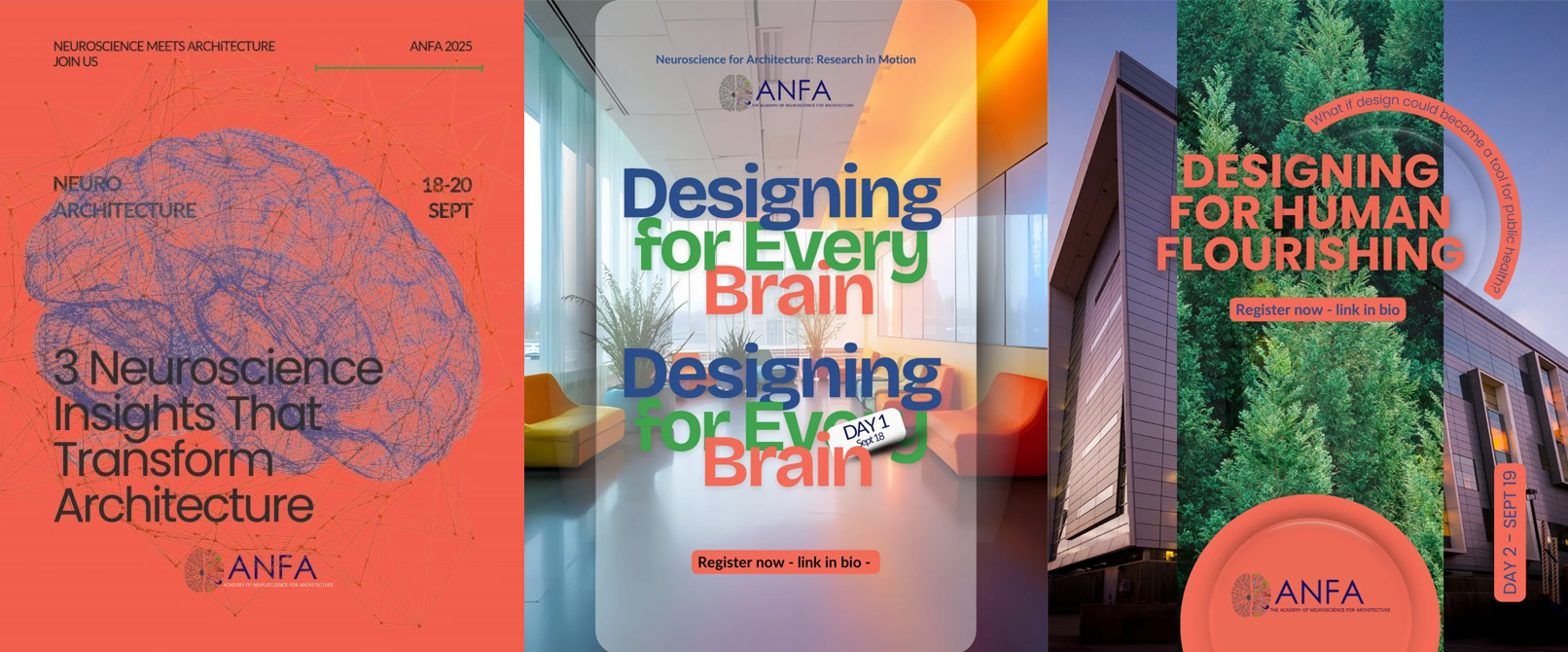

Earlier in September, I had the chance to attend and present at the Academy of Neuroscience for Architecture (ANFA) Conference in La Jolla. ANFA is one of those rare gatherings where architects, neuroscientists, educators, and health experts all come together around a single question: how do the places we design shape how people feel, think, and live?

This year’s theme, “Research in Motion,” captured the energy in the room. The sessions were organized around three big ideas: designing for every brain, designing for human flourishing, and designing for a changing world. We moved from conversations about inclusion and neurodiversity, to health and well-being, to climate change and technology. By the end of three days one thing was clear: research is not meant to sit still in a lab, but to move outward into practice.

Why this matters for our practice

At WRNS, we often ask how our projects can do more than meet a program. How can they spark curiosity in a classroom, or encourage connection on a campus, or support recovery in a health space? The conversations at ANFA reinforced that these instincts have scientific weight. Below are some examples of how this research relates to the way we practice architecture at WRNS Studio:

Education

Current research shows how things like flexible classrooms, sensory-rich environments, well-defined thresholds, curved shapes, and designs that give more choice and agency to the user can support a more supportive learning environment. This work feels especially urgent against the backdrop of alarmingly high rates of anxiety and stress-related health issues among young people. The solution is not simply medical and psychological. The spaces we design play a powerful role in supporting their resilience and well-being. Our designs at WRNS showcase what we instinctually know, but the specificity of the data will help us sharpen our pencils to create better environments.

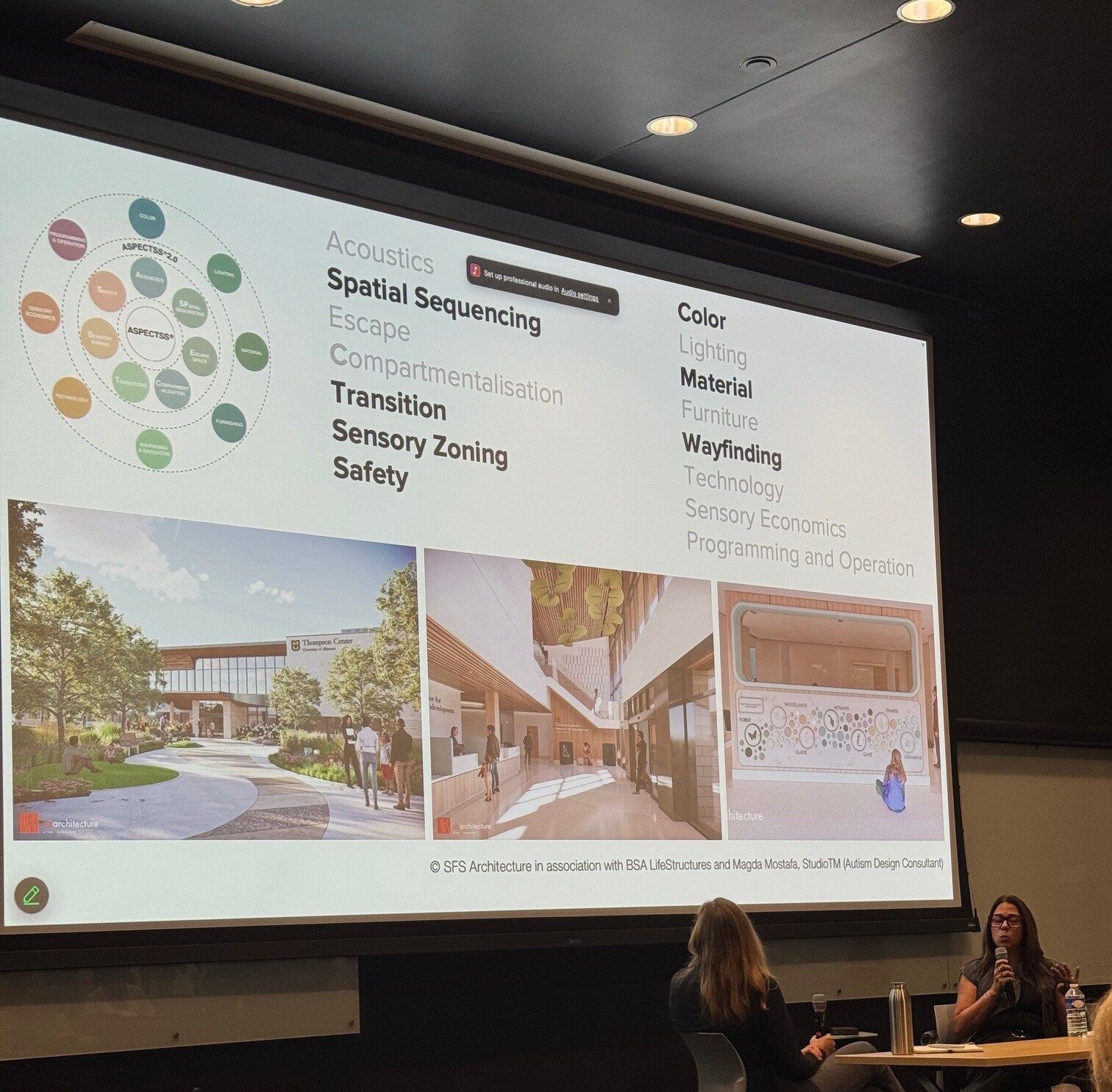

Health and well-being

Studies on daylight, acoustics, and access to nature confirm what we see in practice. These aren’t luxuries but baseline conditions for resilience. The neuroscientific research emphasizes how spatial qualities can reduce stress, improve recovery times, and lower blood pressure. Conversations around hospitals, workplaces, and public spaces all pointed to the same conclusion: environments can either tax our nervous systems or help restore them. For us, this highlights how design decisions at every scale, whether choosing materials, shaping circulation, or opening views to nature, carry measurable health implications.

Climate and Sustainability

It is a well-known fact that sustainable strategies also support cognitive performance and comfort. They go together. However, only recently we’re learning more about the measurable mental health impacts of climate change; not only rising eco-anxiety, but also the trauma associated with climate-related disasters. Events like wildfires, floods, and the release of toxic building materials during these incidents create both immediate physical dangers and lasting emotional scars. It’s a reminder that environmental design and human design are inseparable, and that resilient, healthy buildings can safeguard mental health as well as physical well-being.

My contribution

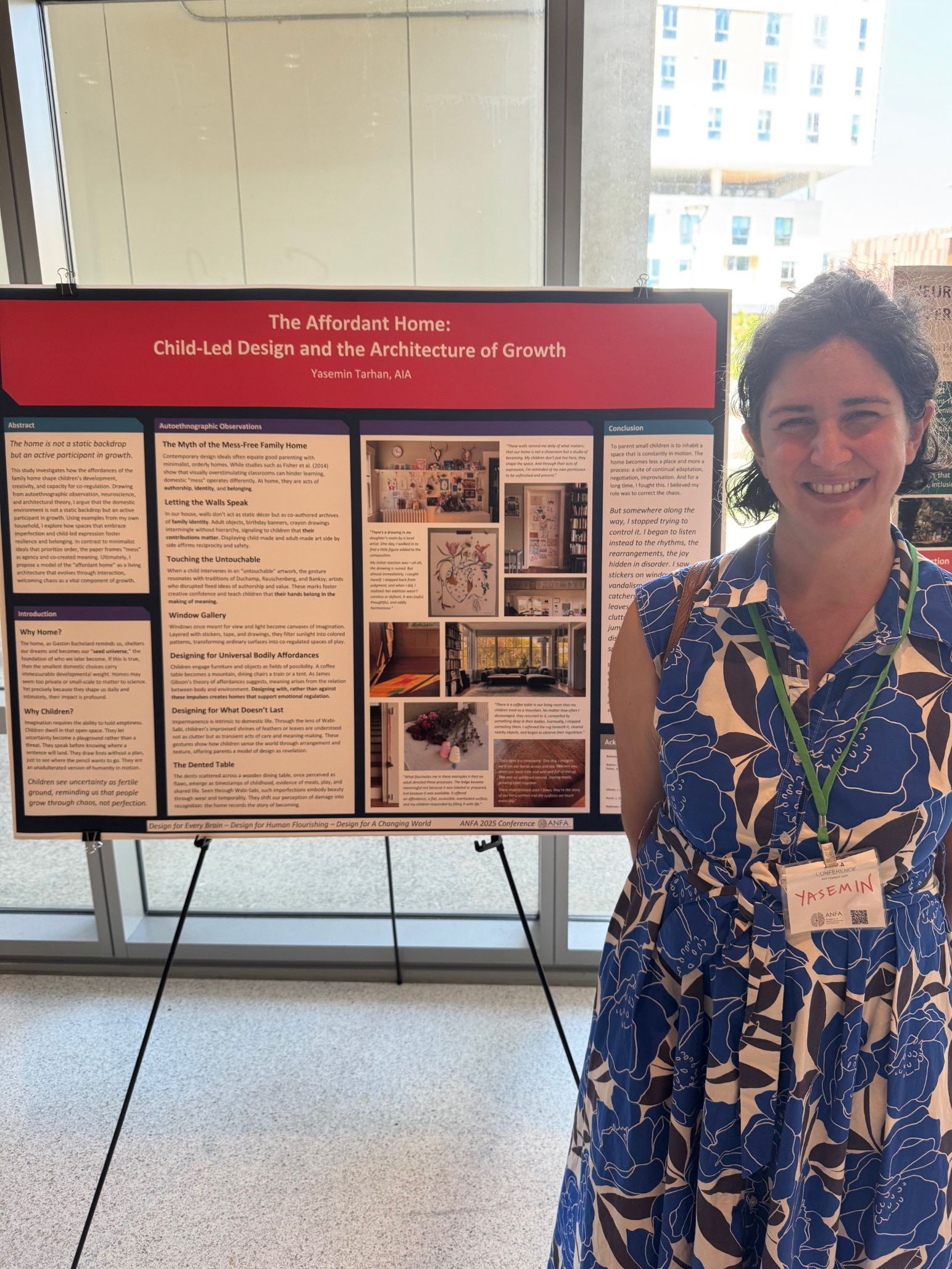

I presented my research titled: The Affordant Home: Child-Led Design and the Architecture of Growth, which explores how everyday domestic environments function as living laboratories for development. The core idea is simple: when spaces invite action through availability, scale, texture and visibility, children co-author their environments. That participation fosters agency, co-regulation, and skill building. While my case study is the home I live in with my three children, the implications are far reaching: classrooms, libraries, work and public spaces can all be designed to scaffold greater agency and participation, not just compliance.

Takeaways

Coming back to WRNS, my biggest takeaway is that neuroscience is not a niche interest. It’s a tool we can fold into our everyday design process. Just as we track energy use or daylight levels, we can also track: how will this space impact stress recovery, healthier movement, or social connection? There is an abundance of scientific research and data we can use to back up these correlations.

If ANFA 2025 was about research in motion, then our role is to keep that motion alive in our work. In every project, small or large, we must remember to design environments that are equitable, healthy, and resilient for every brain. That means building with an awareness of mental health and neurodiversity, and with a commitment to spaces that foster resilience and belonging across all communities.